2023. április 29., szombat

2023. április 28., péntek

2023. április 26., szerda

Kínai Munkás Testület/Chinese Labour Corps (中國勞工旅)

Az előző cikkben szóba került az I. Világháború alatt szolgáló kínai munkáshadsereg, így mivel a Kínai Köztársaság ideje alá tartozó dologról van szó, ebben a cikkben jobban is szemügyre vesszük ezt a témakört.

Az első világháború előrehaladtával a nagyhatalmaknak egyre több nehézséget okozott, hogy fenntartsák a világszerte zajló nagyszabású hadjáratok támogatásához szükséges létszámot. Ugyanakkor Kína - bár hivatalosan semleges volt - ki akarta használni a háborút, hogy új nemzetközi hatalomként pozícionálja magát. Liang Shiyi, a kormány egyik tanácsadója javasolta a "munkaerő-tervet": egy olyan lehetőséget, amellyel Kína a szövetséges hatalmakhoz kapcsolódhatott volna nem katonai személyzet szállításával, hogy enyhítse a munkaerőköltségeiket.

A Kínai Munkás Testület (CLC; franciául: Corps de Travailleurs Chinois; egyszerűsített kínai: 中国劳工旅; hagyományos kínai: 中國勞工旅; pinyin: Zhōngguó láogōng lǚ) a brit kormány által az első világháborúban toborzott munkáshadsereg volt, amely segéd- és fizikai munkavégzéssel segített a katonáknak, hogy elégséges számban juthassanak ki a frontra. A francia kormány is jelentős számú kínai munkást toborzott, és bár a franciáknak dolgozó munkásokat külön toborozták, és nem voltak a CLC részei, a kifejezést gyakran mindkét csoportra használják. Összesen mintegy 140 000 férfi szolgált mind a brit, mind a francia erőknél a háború befejezése előtt, a legtöbbjüket pedig 1918 és 1920 között hazatelepítették Kínába. A CLC-t azok a munkások alapították, akik a Brit erőknél alá voltak beosztva!

Miközben 1914 Július 28-án az Osztrák-Magyar Monarchia hadat üzent Szerbiának, az alig 4 éves Kínai Köztársaság kinyilvánította a konfliktus iránti semlegességét. Eközben Jüan Sikai kínai elnök titokban lobbizott Nagy-Britanniánál, hogy engedje be Kínát a háborúba annak függvényében, ha ezáltal a köztársaság visszakaphatja a Shandong tartományban lévő Qingdao gyarmatot, amelyet Németország 1898-ban foglalt el. Jüan 50 000 kínai katonát ajánlott fel a brit nagykövetnek, de Nagy-Britannia elutasította az ajánlatot. Londonnak kereskedelmi befektetései és koncessziói voltak Kínában, de ne feledkezzünk meg a hongkongi koronagyarmatról sem. A brit háborús kabinet azt akarta, hogy Kínának ne legyen befolyása arra, hogy megszabaduljon ezektől a létfontosságú gazdasági érdekeltségektől - mondja Hszu. A brit tisztviselők attól is tartottak, hogy a kínai követelések arra ösztönöznék az erősödő indiai nacionalistákat Nagy-Britannia legnagyobb gyarmatán, hogy nagyobb önrendelkezésért agitáljanak - mondja Xu.

Kína vezetése továbbbra is küzdött az ország régióinak többsége felett uralmat gyakorló hadurakkal. A törékeny köztársaságot a szétesés veszélye fenyegette. Kína vezetőinek erősnek kellett tűnniük, és a Nagy Háború lehetőséget teremtett erre. Ha Kínának sikerült volna bekerülnie a háborúba és tárgyalóasztalhoz ülnie, az rendkívüli módon megszilárdította volna hatalmi igényeit. "Habár Európa azt mondta, hogy nincs szüksége kínai katonákra, de munkásokra mindenképpen égető szükségük volt." - érvelt Jüan elnök tanácsadója, Liang Shiyi.

1915-ben Liang ismét felkereste az orosz, a francia és a brit nagykövetet. Kína több tízezer fegyvertelen munkást biztosított volna, cserébe azért, hogy részt vehessen a háború utáni konferencián. A franciák és az oroszok beleegyeztek. A britek először elutasították az ajánlatot, de egy évvel később meggondolták magukat.

ENG: In the previous article we discussed the Chinese Labour Corps serving during World War I, so as this is something that falls under the Republic of China period, we will take a closer look at this today.

As the First World War progressed, the great powers found it increasingly difficult to maintain the numbers needed to support large-scale campaigns around the world. At the same time, China, although officially neutral, wanted to use the war to position itself as a new international power. Liang Shiyi, an adviser to the government, proposed the 'manpower plan': a way in which China could link up with the Allied powers by supplying non-military personnel to ease their labour costs.

The Chinese Labour Corps (CLC; French: Corps de Travailleurs Chinois; simplified Chinese: 中国劳工旅; traditional Chinese: 中國勞工旅; pinyin: Zhōngguó láogōng lǚ) was a labour army recruited by the British government in World War I to help soldiers get to the front in sufficient numbers by providing unskilled and manual labour. The French government also recruited a significant number of Chinese workers, and although the workers who worked for the French were recruited separately and were not part of the CLC, the term is often used to describe both groups. In total, some 140,000 men served in both British and French forces before the end of the war, most of whom were repatriated to China between 1918 and 1920. The CLC was founded by workers who were subordinate to the British forces!

While the Austro-Hungarian Empire declared war on Serbia on 28 July 1914, the Republic of China, barely 4 years old, declared its neutrality towards the conflict. Meanwhile, Chinese President Yuan Sikai was secretly lobbying Britain to allow China into the war on the condition that it would allow the republic to regain the colony of Qingdao in Shandong province, which Germany had seized in 1898. Yuan offered 50,000 Chinese troops to the British ambassador, but Britain refused the offer. London had trade investments and concessions in China, but let us not forget the Crown Colony of Hong Kong. Britain's war cabinet wanted to ensure that China had no leverage to get rid of these vital economic interests, says Xu. British officials also feared that Chinese demands would encourage rising Indian nationalists in Britain's largest colony to agitate for greater self-determination, says Xu.

China's leadership continued to struggle with the warlords who controlled most of the country's regions. The fragile republic was in danger of disintegration. China's leaders needed to appear strong, and the Great War provided an opportunity. If China had managed to get into the war and sit down at the negotiating table, it would have consolidated its claims to power in an extraordinary way. "Even though Europe said it didn't need Chinese soldiers, it certainly needed workers badly," argued President Yuan's adviser Liang Shiyi.

1915-ben Liang ismét felkereste az orosz, a francia és a brit nagykövetet. Kína több tízezer fegyvertelen munkást biztosított volna, cserébe azért, hogy részt vehessen a háború utáni konferencián. A franciák és az oroszok beleegyeztek. A britek először elutasították az ajánlatot, de egy évvel később meggondolták magukat.

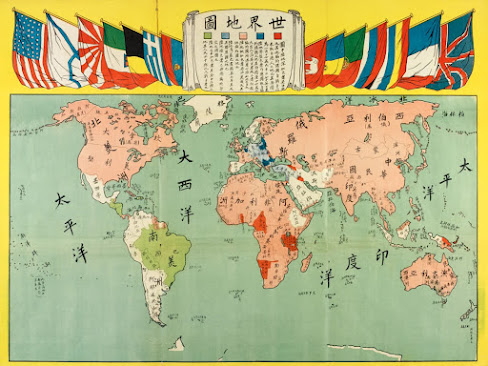

Kínai világtérkép. A szövetséges nemzetek pirossal és az ellenségesek kékkel vannak jelölve, 1918

Chinese map of the world with allied nations in red and the enemies in blue, 1918

A TOBORZÁS/RECRUITING

Georges Truptil francia alezredes 50 000 kínai munkás toborzását tűzte ki célul. Az első, 1698 kínai újoncból álló csoport 1916. augusztus 24-én indult el Tianjin kikötőjéből a dél-franciaországi Marseille-be. Ekkorra Nagy-Britannia is úgy döntött, hogy elkezdi a kínai munkások toborozását. "Még a kínai szótól sem riadnék vissza a háború végrehajtása céljából" - mondta Winston Churchill parlamenti képviselő 24 évvel azelőtt, hogy miniszterelnök lett volna. "Ezek azok az idők, amikor az embereknek a legkevésbé sem kell félniük az előítéletektől".

A brit toborzás 1916 novemberében kezdődött a Shandong tartománybeli Weihaiwei koncessziójában, majd később a japánok által megszállt Qingdaóban. Liang eközben Japánba utazott, hogy felajánlja a kínai munkásokat szolgálatait, tőkéért és technológiáért cserébe. A britek szinte azonnal kizárták a hongkongi toborzást, miután a gyarmat kormányzója, Francis Henry May Londonba küldött távirataiban ellene érvelt. A helyi kínai lakosság "maláriával fertőzött" és nem "fegyelmezhető" - írta indoklás gyanánt a londoni gyarmati titkárnak.

Ennek ellenére néhány hongkongi mégis a francia erőknek dolgozott. A Huimin társaság 3221 munkást toborzott, és a Limin, egy másik francia társaság további 2000 embert vett fel Hongkongban. A legtöbb munkás Shandong és Hebei tartományokból érkezett. Sokan a német gyarmatosítók által épített vasútvonalon utaztak, amely a toborzottakat az egykori német kikötőbe, Qingdaóba vitte.

A Kínai Munkás Testület jelvénye, 1917-1920. Fotó: In Flanders Fields Museum, Ypres

Badge from the Chinese Labour Corps, 1917-1920. Photo: In Flanders Fields Museum, Ypres

French Lieutenant-Colonel Georges Truptil set out to recruit 50,000 Chinese workers. The first group of 1,698 Chinese recruits left the port of Tianjin for Marseille in the south of France on 24 August 1916. By this time, Britain had also decided to start recruiting Chinese workers. "I would not shrink from even the word Chinese to carry out the war," said Winston Churchill MP 24 years before he became prime minister. "These are the times when people need have the least fear of prejudice".

British recruitment began in November 1916 in the Weihaiwei Concession in Shandong province, and later in Japanese-occupied Qingdao. Liang meanwhile travelled to Japan to offer his services to Chinese workers in exchange for capital and technology. The British almost immediately ruled out recruiting Hong Kong after the colony's governor, Francis Henry May, argued against it in telegrams to London. The local Chinese population is 'malarial' and cannot be 'disciplined', he wrote to the colonial secretary in London, giving his reasons.

Nevertheless, some Hong Kongers still worked for the French forces. The Huimin company recruited 3,221 workers, and Limin, another French company, recruited a further 2,000 in Hong Kong. Most of the workers came from Shandong and Hebei provinces. Many travelled on the railway line built by the German colonialists, which took recruits to the former German port of Qingdao.

A kínaiak vonatokon és hajókon jutottak el Európába. Százak, ha nem ezrek haltak meg útközben. Xu becslései szerint legalább 700-an vesztek oda. Csak 1917. február 17-én 400-600 munkás halt meg, amikor egy német tengeralattjáró elsüllyesztette az Athos francia utasszállító hajót Málta közelében. Li kutatásai szerint még többen haltak meg Oroszországon átkelve.

Xu becslése szerint 1916 és 1920 között körülbelül 3000 kínai munkás halt meg Franciaországban, útban a nyugati frontra, Észak-Franciaországba, vagy éppen visszatérve Kínába. A Jinan Egyetem tudósa, Li becslése szerint akár 30 000 kínai is meghalhatott az orosz fronton.

Hat héttel az Athos elsüllyedése után a kínai munkások első kontingense az RMS Empress of Russia fedélzetén érkezett meg Vancouverbe. Ott vonatra szálltak, és több mint 6000 kilométert utaztak a kanadai Atlanti-óceán partján fekvő Montrealba, St Johnba vagy Halifaxba. "Úgy terelték őket a vagonokba, mint a marhákat, megtiltották nekik, hogy elhagyják a vonatot, és úgy őrizték őket, mint a bűnözőket" - számolt be a Halifax Herald 1920-ban, amikor a szállítások véget értek, és a kanadai cenzúra engedélyezte a tudósítást.

A Kínai Köztársaság éberen figyelte a külföldön dolgozó munkásait.

1917-ben Kína létrehozta a tengerentúli kínai munkások irodáját, hogy foglalkozhasson a munkások esetlegesen felmerülő panaszaival. Egy esetben Li Jun követ tiltakozott amiatt, hogy a francia kormány lóhússal etette a kínai munkásokat, egy másik pekingi beavatkozás után Nagy-Britannia kártérítést nyújtott a munkásoknak a munka során elszenvedett vakság, süketség vagy "gyógyíthatatlan elmebaj" esetén.

1919-re a Post becslése szerint a munkások 6 millió font megtakarítást vittek haza, ami ma nagyjából 17,3 milliárd HK$. Kína franciaországi nagykövete, Hu Weide reményét fejezte ki, hogy a nagyon szükséges technikai tudással felvértezett munkások hazatérve fejleszteni fogják Kína gazdaságát. "A legjobbak, akik esetleg megismerhetik a francia gyárak vezetését, kiváló menedzserekké válhatnak Kínában, amikor visszatérnek" - írta akkoriban egy táviratban, amelyet ma is a kínai kormány archívumában őriznek.

Xu történész szerint Peking érdeklődése ezen parasztok iránt politikai jellegű is volt.

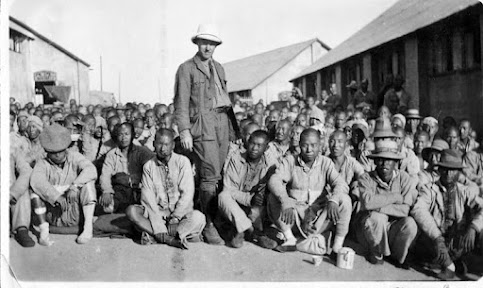

Munkások Weihai-ban a toborzás során. Fotó: Weihai Archives

Workers seen in Weihai during recruitment. Photo: Weihai Archives

A kínai munkaszolgálatosok egy brit tiszt felügyelete mellett zabzsákokat rakodnak egy teherautóra Boulogne-ban (1917. augusztus 12.)

Men of the Chinese Labour Corps load sacks of oats onto a lorry at Boulogne while supervised by a British officer (12 August 1917)

A munkaszolgálatosok és egy brit katona egy roncs Mark IV-es harckocsit beleznek ki alkatrészekért, amiket majd a páncélosok központi raktárában, Teneurben tudnak hasznosítani, 1918 tavaszán.

Labour Corps men and a British soldier cannibalise a wrecked Mark IV tank for spare parts at the central stores of the Tank Corps, Teneur, spring 1918.

A LETELEPEDÉS, MINT OPCIÓ/THE CHOICE TO STAY

Az Egyesült Államok 1917. áprilisi hadba lépésével Nagy-Britanniának és Franciaországnak immáron nagyobb szüksége volt az amerikai katonák szállítására, a kínai munkások így másodlagos szempont lettek. Kína felhagyott semlegességével, majd augusztusban hadat üzent Németországnak és az Osztrák-Magyar Monarchiának, hogy részt vehessen a háború utáni tárgyalásokon. Oroszország kilépett a háborúból, amikor a cári birodalom 1917 októberében, a világ első kommunista forradalmában összeomlott, és kínai munkások százezrei rekedtek az egykori birodalomban. Tíz nappal Németország 1918. november 11-i kapitulációja előtt Nagy-Britannia visszaküldte a 365 kínai munkás első csoportját, és ezzel megkezdődött a hazatelepítés, amely 1920 szeptemberében ért véget.

A háború végére a kínaiak már elkezdték a saját közösségeiket kialakítani Franciaországon belül, a köztársaságban maradt munkások sokat segítettek a harcok utáni újjáépítésben. Körülbelül 3000 kínai munkás maradt Franciaországban és telepedett le, egész kínai városrészeket kialakítva. Achiel van Walleghem belga pap emlékirataiban feljegyezte, hogy a boltosok elkezdtek kínaiul tanulni, hogy kiszolgálják ezeket az új vásárlókat. A londoni Imperial War Museumban őrzött videofelvételeken megfigyelhető az is, hogy a franciaországi kínai munkások gólyalábakon hagyományos operát és táncot adnak elő.

ENG: With the entry of the United States into the war in April 1917, Britain and France now had a greater need to supply American troops, and Chinese workers became a secondary consideration. China abandoned its neutrality, and in August declared war on Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire to participate in post-war negotiations. Russia pulled out of the war when the Tsarist empire collapsed in October 1917, in the world's first Communist revolution, leaving hundreds of thousands of Chinese workers stranded in the former empire. Ten days before Germany's surrender on 11 November 1918, Britain sent back the first group of 365 Chinese workers, marking the beginning of the repatriation that ended in September 1920.

Kínai előadók szórakoztatják a munkaszolgálatosokat és a brit csapatokat egy szabadtéri színházban Étaples-ban (1918. június).

Chinese performers entertain Labour Corps members and British troops at an open-air theatre at Étaples (June 1918).

Kínaiak szórakoztatják a brit csapatokat Franciaországban. A sárkányok készen állnak a sárkányharcra. Fénykép: National Library of Scotland

Chinese entertain British troops in France. Dragons ready for the Dragon fight. Photo: National Library of Scotland

ENG: The CLC was not directly involved in the fighting. According to records kept by British and French recruiters, some 2,000 CLC died during the war, many in the 1918 influenza epidemic, but some Chinese scholars estimate the number could be as high as 20,000, victims of bombing, mines, poor care or disease.

2023. április 25., kedd

2023. április 24., hétfő

Vecsés/Bonyhád/PSMK makettkupa

A szokásos zsámbéki dátumokon kívül idén több helyen is találkozhattok velünk, így az alábbi 3 helyszínen már biztosan jelen leszünk az idei évben:

2023. április 12., szerda

2023. április 9., vasárnap

Május 4.-e Mozgalom/ May Fourth Movement (五四運動)

.jpg)

13 egyetem közel 3000 diákja tüntetett Pekingben a Tienanmen téren

Around 3,000 students from 13 universities in Beijing gathered in Tiananmen Square

A Versaillesben megkötött békeszerződésnél a kínai delegációnak az alábbi követelései voltak:

- a külföldi hatalmak minden kiváltságának eltörlése Kínában, mint például az extraterritoriális jog

- a japán kormánnyal kötött "huszonegy követelés" visszavonása

- Shandong területének és jogainak visszaadása Kínának, amelyet Japán az első világháború alatt Németországtól elvett.

Amikor 1919 áprilisában Kínában kiderült, hogy a versailles-i békeszerződésről folytatott tárgyalások nem fogják tiszteletben tartani Kína követeléseit, ez olyan mozgalmat indított el, amely még forradalmibbnak tekinthető, mint az, amely a Csing dinasztia birodalmának 8 évvel azelőtt véget vetett.

ENG: At the end of the First World War in 1918, China was convinced that it would be able to recapture the territories occupied by the Germans in what is now Shandong province, and after all, fighting on the side of the Allies, this desire seemed entirely realistic. Unfortunately, the story took a very different turn. The Hadur government of the time secretly made a deal with the Japanese, offering them the German colonies in exchange for financial support, and the Allies in turn recognised Japan's territorial claims in China. The Versailles meeting was dominated by the Western Allies, who paid little heed to Chinese demands. The European delegations, led by French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau, were primarily interested in punishing Germany. Although the US delegation supported Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points and the idea of self-determination, they failed to promote these ideas in the face of stubborn opposition from David Lloyd George and Clemenceau. The American support for self-determination in the League of Nations was attractive to Chinese intellectuals, but the failure of the Americans to follow their ideas was seen as a betrayal. This diplomatic failure at the Paris Peace Conference created what became known as the 'Shandong problem'.

When it became clear to China in April 1919 that the negotiations on the Treaty of Versailles would not respect China's demands, it triggered a movement, even more revolutionary than the one that had ended the empire of the Qing dynasty 8 years earlier.

A Tsinghua Egyetem diákjai japán árukat égetnek.

Tsinghua University students burn Japanese goods.

ENG: During the May Fourth Movement (五四运动, Wusi Yundong), around 5,000 students from Peking University took to the streets to protest against the Treaty of Versailles, but there was much more at stake than the issue of land acquired by the Japanese. The 1911 revolution was merely a regime change, and a close look at it will make it clear to the reader that the aspirations for modernisation and many of the demands of the people were not realised even afterwards. With the emergence of working class support, the May Fourth movement entered a new phase. The centre of the movement shifted from Beijing to Shanghai and the working class replaced the students as the main force of the movement. The Shanghai working class staged a strike on an unprecedented scale. The growing scale and number of participants in the nationwide strike led to paralysis of the country's economy and posed a serious threat to the Beijing government. The nationwide support for the movement reflected the enthusiasm for nationalism and national renewal that was also the basis for the development and spread of the May Fourth Movement. Benjamin I. Schwartz added: "Nationalism, which was of course the defining passion of the May Fourth, was not so much a separate ideology as a shared inclination."

A Pekingi Normal Egyetem diákjai, miután a kormány őrizetbe vette őket a május negyedik mozgalom idején.

Students of Beijing Normal University after being detained by government during the May Fourth Movement.

Ugyanekkor az Új Kultúra Mozgalomban egyesült értelmiségiek arra törekedtek, hogy a kínai kultúrát a hagyományos tudós hivatalnokokon túli társadalmi csoportok számára is hozzáférhetőbbé tegyék. Ennek érdekében irodalmi forradalmat szorgalmaztak, amelyben a wenyan 文言, az írott nyelv megcsontosodott rendszerét a népnyelvre épülő, úgynevezett baihua 白话 rendszerrel akarták felváltani. Hu Shi az egyik tudós akit ezzel a mozgalommal azonosítanak, míg Lu Xunt az 1920-as években kialakult írásmód egyik legtermékenyebb gyakorlójának tekintik.

ENG: The May Fourth movement was part cultural revolution, part social movement. On the cultural side, students had been inspired by Western thinking for the previous two decades, which had fuelled frustration and dissatisfaction with Chinese traditions. In the resulting intellectual ferment, people sought answers to the question of why and how China had fallen behind the West. The main reasons were seen in the negative effects of traditional morality, the clan system and Confucianism. China, in its deplorable state, could only be cured by the "two doctors": "Doctor Science and Doctor Democracy".

At the same time, intellectuals united in the New Culture Movement to make Chinese culture more accessible to social groups beyond the traditional scholarly bureaucrats. To this end, they called for a literary revolution, in which they wanted to replace the ossified system of wenyan 文言, the written language, with a system based on the vernacular, known as baihua 白话. Hu Shi is one of the scholars identified with this movement, while Lu Xun is considered one of the most prolific practitioners of the writing system that emerged in the 1920s.

1919. május 4-én reggel tizenhárom különböző helyi egyetem diákképviselői találkoztak Pekingben, és öt határozatot fogalmaztak meg:

Másnap Pekingben, csakúgy mint országszerte a nagyobb kínai városokban, sztrájkba léptek a diákok. Hazafias érzelmű kereskedők és munkások is csatlakoztak a tüntetésekhez. A tüntetők ügyesen fellebbeztek az újságokhoz, és képviselőket küldtek, hogy vigyék az igét az szerte az egész országban. Június elejétől a sanghaji munkások és üzletemberek is sztrájkba léptek, mivel a mozgalom központja Pekingből Sanghajba helyeződött át. Tizenhárom egyetem kancellárjai intézkedtek a diákfoglyok szabadon bocsátásáról, és Cai Yuanpei, a Pekingi Egyetem igazgatója tiltakozásul lemondott.

ENG: On the morning of May 4, 1919, student representatives from thirteen different local universities met in Beijing and formulated five resolutions:

The next day, students in Beijing, as well as in major Chinese cities across the country, went on strike. Patriotic traders and workers also joined the protests. Protesters skillfully appealed to newspapers and sent representatives to take the message across the country. In early June, workers and shopkeepers in Shanghai also went on strike as the movement's headquarters moved from Beijing to Shanghai. The chancellors of thirteen universities have arranged for the release of student detainees, and Cai Yuanpei, the director of Peking University, has resigned in protest.

ENG: Newspapers, magazines, civic associations and chambers of commerce offered their support to the students. Traders have threatened to withhold tax payments if the Chinese government continues to be so stubborn. In Shanghai, a general strike by traders and workers has devastated almost the entire Chinese economy. The Beijing government, under intense public pressure, released the arrested students and dismissed Cao Rulin, Chiang Zongxiang and Lu Zongyu, who were accused of collaborating with the Japanese. In Paris, Chinese representatives refused to sign the Treaty of Versailles: the May Fourth movement won its first victory, which was mainly symbolic, as Japan retained control of the Shandong Peninsula and the Pacific islands for the time being. The partial success of the movement also showed that China's social classes across the country were capable of successful cooperation if given the right motivation and leadership.

Női diáktüntetők/Female student protesters

ENG: May Fourth is credited as the catalyst for the founding of the Chinese Communist Party. Before 1919, people had little interest in what was happening in Russia. After May Fourth, Marxism was seen by one stratum as a viable revolutionary ideology for a predominantly agrarian society such as China was in those years.

Az 1951-es Tavaszi Hadjárat, 9. rész(第五次战役)

LOGISZTIKAI PROBLÉMÁK ÉS AZOK ORVOSLÁSÁRA TETT KÍSÉRLETEK A legfőbb ok, amiért Peng leállíttatta a Tavaszi Offenzívát, az a villámgyo...

-

Idén is megrendezésre kerül a Kenyérzsák túra, azonban immáron nyitott formában, nem csak hagyományőrzőknek! Akit érdekel az esemény, az alá...

-

Before we dive into the various battles of the Korean War and the processes that determined them, let's take a look at the level of de...

-

The Dongjiang Fifth Column , known in full as the Guangdong People's Anti-Japanese Guerrilla Dongjiang Fifth Column , was an anti-Japa...